This article (Definition Of Gothic Architecture: Its Origin, And Division Into Styles) is excerpted from the book entitled "The principles of Gothic ecclesiastical architecture. With an explanation of technical terms, and a centenary of ancient terms." Author: Bloxam, Matthew Holbeche, 1805-1888, Page 17-22.

The appellation of the word “Gothic,” when applied to Architecture, is used to denote in one general term, and distinguish from the Antique, those peculiar modes or styles in which our ecclesiastical and domestic edifices of the middle ages were built. In a more confined sense, it comprehends those styles only in which the pointed arch predominates, and it is then used to distinguish them from the more ancient Anglo-Saxon and Anglo-Norman styles.

The use of the term Gothic, in this country, first appears about the close of the seventeenth century, when it was employed by such writers as Evelyn and Wren, as an epithet intended to convey a feeling of disesteem for the structures of medieval architecture, which even the master mind of Wren was unable to appreciate. It has been since generally followed.

The origin of this kind of architecture may be traced to the classic orders in that state of degeneracy into which they had fallen in the age of Constantine and afterwards. The Romans, on their voluntary abandonment of Britain in the fifth century, left many of their temples and public edifices remaining, together with some Christian churches; and it was in rude imitation of these Roman buildings of the fourth century that the most ancient of our Anglo-Saxon churches were constructed. This is apparent from an examination and comparison of them with the vestiges of Roman buildings still existing.

No specific regulation has been adopted, with regard to the denomination or division of the several styles of English Ecclesiastical Architecture, in which all the writers on the subject agree : hut they may be divided into seven, which, with the periods when they flourished, are defined as follows:

The Anglo-Saxon style prevailed from the mission of St. Augustine at the close of the sixth to the middle of the eleventh century.

The Anglo-Norman style may be said to have prevailed generally from the middle of the eleventh to the latter part of the twelfth century.

The Semi-Norman, or Transition style, appears to have prevailed during the latter part of the twelfth century.

The Early English, or general style of the thirteenth century.

The Decorated English, or general style of the fourteenth century.

The Florid, or Perpendicular English, the style of the fifteenth, and early part of the sixteenth century.

The Debased English, or general style of the latter part of the sixteenth, and early part of the seventeenth century, towards the middle of which Gothic architecture, even in its debased state, appears to have been almost discarded.

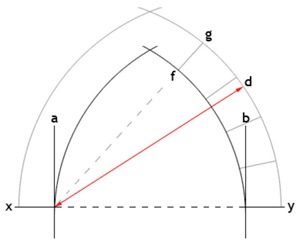

The difference of these styles may be distinguished partly by the form of the arches, which are semi-circular or segmental, simple or complex pointed, though such forms are by no means an invariable criterion; by the pitch and construction of the roof, by the size and shape of the windows, and the manner in which they are subdivided or not, by mullions and tracery; hut more especially by certain details, ornamental accessories and mouldings, more or less peculiar to each.

The majority of our cathedral and country churches have been built, or added to, at different periods, therefore they seldom exhibit an uniformity of design ; and many have parts about them of almost every style. There are, however, numerous exceptions of churches erected in the same style through-out ; and this is more particularly observable in those of the fifteenth century.

The general ground plan of cathedral and conventual churches was after the form of a Cross, the edifice consisting of a central tower, with transepts running north and south; westward of the tower was the nave or main body of the structure, with AISLES. The WEST FRONT contained the principal entrance, and was frequently flanked by towers. Eastward of the central tower was the CHOIR also with aisles, where the principal service was performed, and beyond this was the LADY CHAPEL. The design also sometimes comprehended other chapels. On the north or south side, generally on the latter, was the CHAPTER HOUSE, in early times quadrangular, but afterwards octagonal in plan; on the same side, in most instances, were the CLOISTERS, which communicated immediately with the church, and surrounded a quadrangular court, bounded on the side parallel with the church by the refectory. The chapter house and cloisters we still And remaining as adjuncts to most cathedral churches, though the conventual buildings of a domestic nature, with which the cloisters formerly also communicated, have generally been destroyed. Mere parochial churches have commonly a tower at the west end, a nave, aisles, north and south porches, and a CHANCEL. Sometimes the tower is at the west end of one of the aisles, or at the side; occasionally we find it altogether detached from the church. Sometimes a turret occurs near the east end of the north or south aisle, containing a staircase which led to the Roodloft. Some churches have transepts; and to many have been annexed, at the cost of individuals, small side chapels or additional aisles, to serve for burial places and chantries. Over some few of these chantry chapels are chambers containing fireplaces, and so constructed with regard to their access, which can only be obtained through the church, as to form a “domus inclusa,” or residence for a priest. To some churches a “Vestiarium,” or vestry room, is attached; the usual position of this is on the north side of the chancel; sometimes we meet with it behind the altar, but we very seldom find it on the south side of the chancel, though there are instances of its being thus placed, and it has rarely an external entrance. The position of the porch is towards the west or the north or south side of the church; it has generally one bay or window intervening between it and the west wall. In some few instances it is placed close to the extreme west, but this is not appropriate. Many porches contain rooms over them. The smallest churches have a nave and chancel only, with a small bell-turret formed of wooden shingles, or an open arch of stonework on the gable at the west end. The eastern apex of the roof of the chancel was always surmounted by a stone cross.

Provincialisms often occur in the churches of particular districts; these appear to have sometimes originated from the building materials of the locality, sometimes from the small and scattered population. In the Isle of Wight, where timber appears to have been scarce, very little is used in the construction of the churches, and many of the porches are covered with stone slabs, supported by arched ribs without any framework of wood, the mouldings over doorways and windows are likewise unusually bold. In some parts of Essex, from the want of stone, the churches are poor in architectural display, and many of the belfries are of wood. In the north of Herefordshire, a thinly inhabited district, we meet with many small plain Norman or Early English churches, consisting only of a nave and chancel, with sometimes a low square Early English tower superadded, rising only to the ridge of the roof of the nave. In Wales they generally are exceedingly plain and poor, the material being of a stone not suitable for mouldings, and many of the church towers are very plain in construction and without buttresses, the masonry consisting of rag, some are furnished with an embattled parapet, and some are covered with a pyramidical roof. In the south of Northamptonshire we have a number of plain Decorated churches of a similarity of character, and there are likewise rich ones in the same style. In this county we may trace more gradually perhaps than in any other the changes in ecclesiastical architecture, step by step, from the seventh century down to the Reformation. Early English and Decorated spires abound in the northern parts of the county. In some parts of Lincolnshire, fine and costly decorated churches with spires prevail. In this county we also find many late examples of a transitional character of Anglo-Saxon work. Somersetshire is rich in churches of the fifteenth century, of the Perpendicular style, with lofty towers more or less covered by panel work, and the spires are few. In some districts the aisles of many of the churches are extended eastward as far as the east wall of the chancel. In other parts of the country provincialisms are also found.